Andrew Cartwright—The Outer Banks’ Missionary to Africa

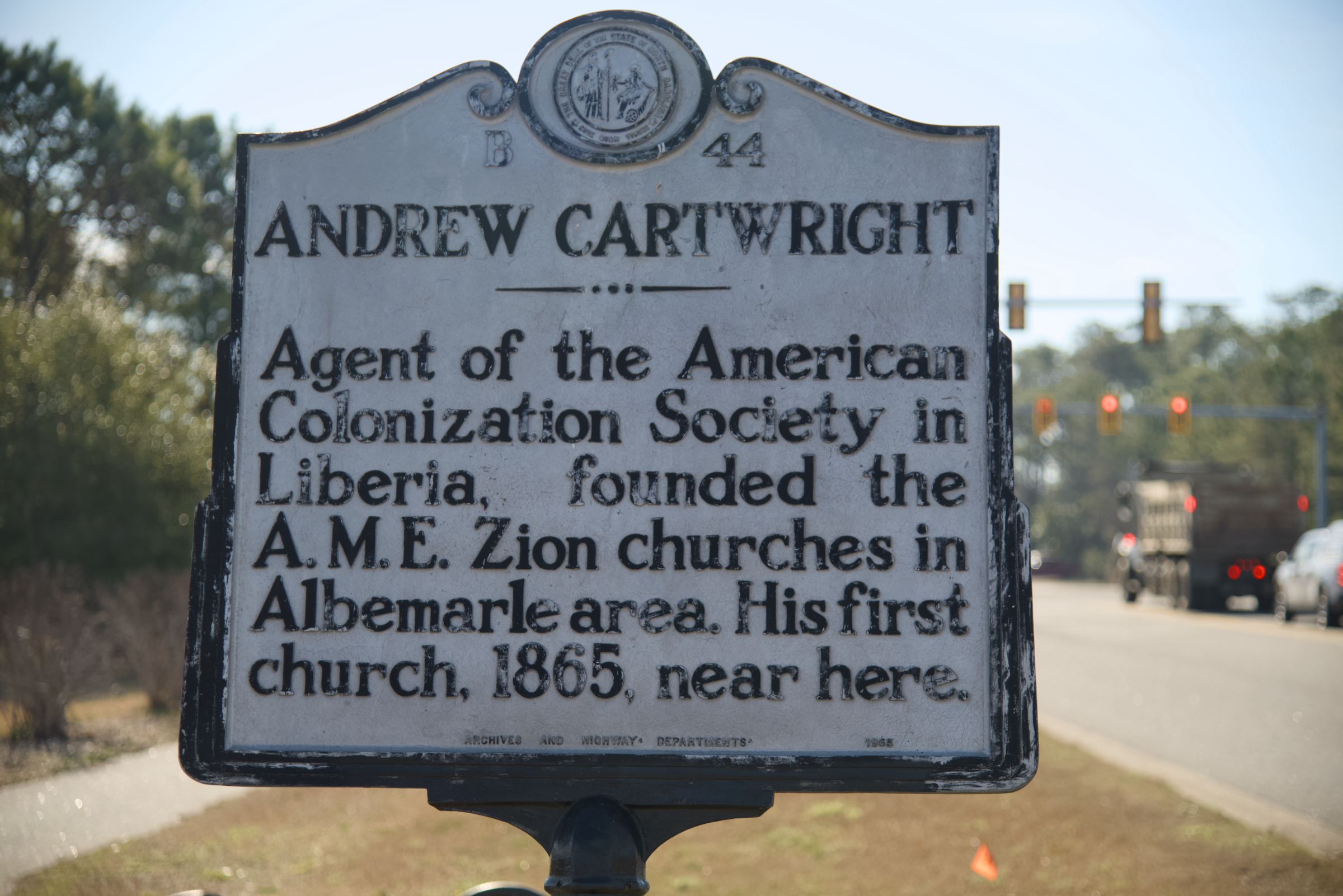

Just a little past the intersection of US 64 and old US 64 as it heads to Manteo, there’s a historic marker telling the story of Andrew Cartwright. The sign is brief and only hints at the full story.

“ANDREW CARTWRIGHT Agent of the American Colonization Society in Liberia, founded the A.M.E. Zion churches in Albemarle area. His first church, 1865, near here. NC 345 at US 64/264 southeast of Manteo,” the sign reads.

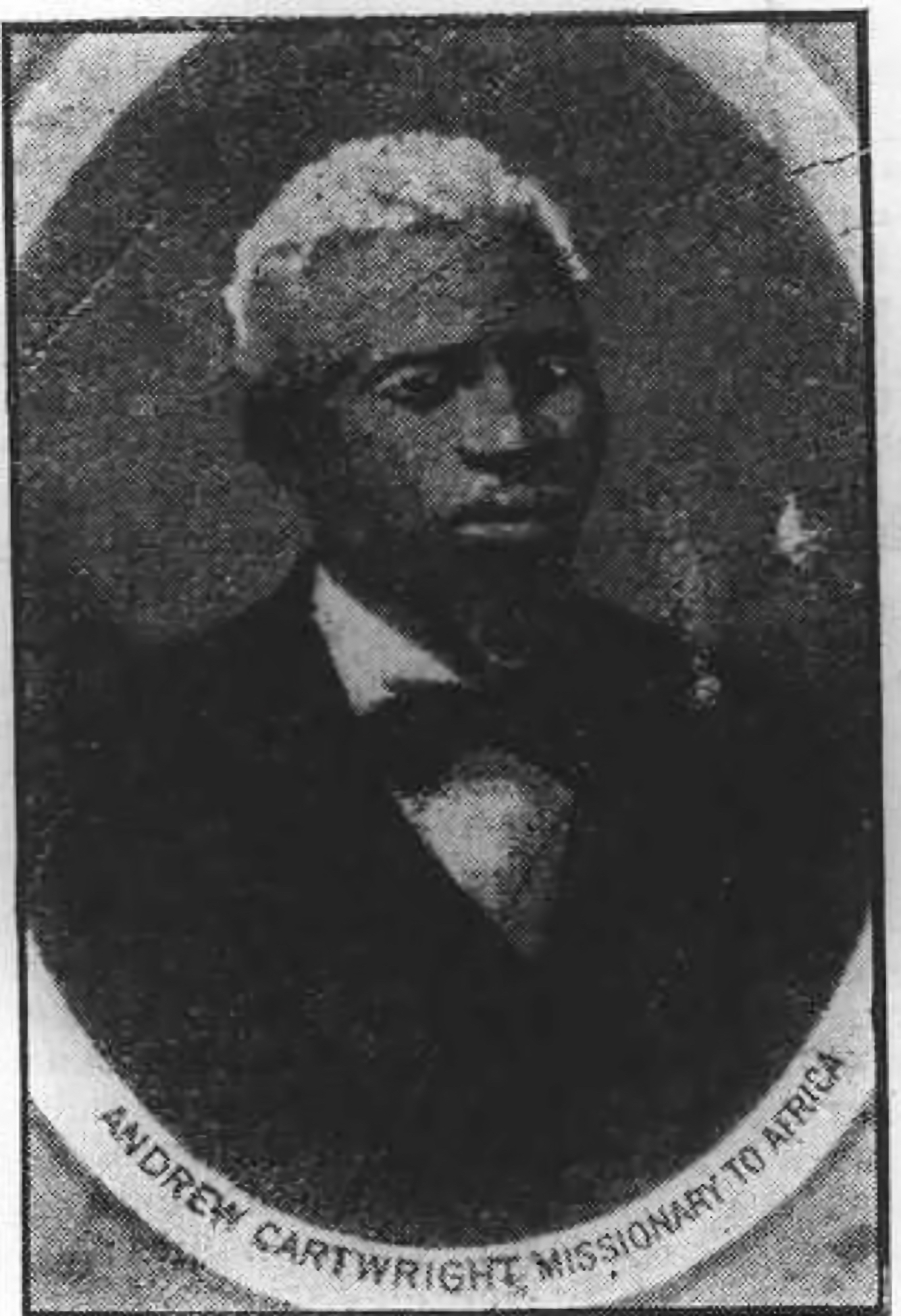

Although there are no records of his birth, there is reason to believe Cartwright was born enslaved in Elizabeth City, North Carolina, in 1834. At some point before the Civil War, Cartwright escaped, fleeing to New England where he learned to read and write and became an ordained minister in the AME Zion church.

He returned to North Carolina as Union forces took control of the eastern part of the state. By 1864, he was teaching at the Roanoke Island Freedmen’s Colony.

In his autobiography, “A brief history of the slave life of Rev. L.R. Ferebee,” Ferebee places Cartwright at the colony writing, “Some time in May (1864), Rev. Andrew Cartwright lectured the Sabbath School on the subject of Repentance,” he wrote.

The Roanoke Island church was the first of 12 churches Cartwright founded throughout northeastern North Carolina in 10 years. Although the buildings no longer stand, some of the congregations are still part of the AMEZ family.

The 1870s. though, marked the end of Reconstruction and the beginning of the Jim Crow laws that would dominate Southern politics until the 1970s, and Cartwright, despairing of equality between the races in this nation, felt there was no hope for reconciliation.

By 1871, Cartwright was advocating for African Americans to emigrate to Africa. Cartwright was named president of the Freedmen’s Emigrant Society in March of that year.

The Society published a constitution that called for African Americans “to aid each other to obtain a home in Liberia…”

Included with the constitution was an address “To our Brethren of African Descent.” Authored in part by Cartwright, it described a bleak future for Blacks who would not leave the United States, telling them, “whenever any people were carried into captivity they never prospered nor attained to eminence until they returned to their ancestral land…”

And then going on to decry the state of race relations in 1871 America.

“What have we to hope for by staying in the United States? There are but few of us any better off now than we were five years ago. Most of us are not so well off, and our condition is becoming more and more oppressive every year.”

The Society’s information was published in the May edition of the African Repository, the American Colonization Society (ACS) publication, which is significant.

The ACS was created in 1816, and it is the reason Liberia came into existence. The organization’s aim was to return free people of color to Africa. At first, it had widespread support. Slaveholders saw the organization as a way to rid themselves of free people of color who reminded their human property that freedom was possible. Abolitionists believed the colony would give free people of color a new start in life and avoid the issue of equality between the races.

However, the ACS did not have the resources to support a colonization effort in Africa, and American immigrants were not welcomed in Liberia. Making matters worse, the alliance of abolitionists and slaveholders fell apart; abolitionists saw the ACS as an excuse for slaveholders to hold their property in bondage, and slaveholders weren’t about to free anyone just so they could return to Africa.

The ACS, however, did not fade quickly into oblivion and survived well into the 20th century, finally dissolving in 1964.

Although Cartwright believed African-Americans should emigrate to what he viewed as their motherland, this idea never gained the traction he hoped it would. As early as 1849, Frederick Douglass, perhaps the most important voice of 19th-century Black America, made it clear that, “as a people, the colored man has had a place upon the American soil.”

Sailing for Africa in 1877, Cartwright enjoyed moderate success at first. He settled in Brewerville, a small town eight or nine miles north of Monrovia, the country’s capital.

Cartwright’s missionary work, however, was not approved by the AMEZ church. A trip to the United States and a meeting with church leadership led them to support him in 1880, but that support quickly waned. By the middle of the 1880s, his salary had been reduced by half.

A master, though, at self-promotion, he prolifically wrote letters to the editor of The Star of Zion, the publication of the AMEZ church.

In 1885, he wrote a glowing letter about his work, telling readers, “I find the young people take great delight in a church ruled and governed by colored leaders or black bishops. It will not be long, I believe, before a great change will take place in this country, and if we only work up, this change will be for the good of Zion.”

An 1895 visit from a newly appointed bishop for the AMEZ church in Africa called into question Cartwright’s ministry, finding it, according to Bishop John Small, in “poor condition.”

Cartwright again turned to the letters to the editor page of the Star of Zion, writing, “What has A. Cartwright done to be treated like this…”

His mission never extended much beyond Brewerville, but he was the first of his AMEZ church to go to Liberia. He remained at his post until he passed away on January 14, 1903, falling “quietly into the arms of death between twelve and one o’clock p.m.…” his wife wrote in the Star of Zion.