The bones of ships are constantly sinking beneath the sands of the Outer Banks, then reappearing to be swallowed once again by the sands. Down on Ocracoke Island, that process seems to happen a little bit more than other places along the Outer Banks, although that might be because it’s a more limited space.

Whatever the reason, two shipwrecks have risen from the sand in the past three months. Back in November, the George W. Wells reappeared toward the north end of the island. Sinking in 1913, she was a six-masted schooner and one of the largest ever built.

More recently, just north of the pony pens on the island, another wreck is again visible. At this point, no one is sure what ship it was; the best guess is the schooner Nomis that sank in 1935. Another possibility is that it’s the 1837 wreck of the steamer Home, although the final moments of the ship’s death would seem to make that improbable.

Yet if it is the Home, there is a horrific story to be told.

Built in 1836, the steamship Home was 220′ long, weighing in at 550 tons, and she was originally designed for the river trade. After her launch, though, she was quickly converted to a luxury ocean packet complete with mahogany and cherrywood paneled staterooms, skylights, and saloons.

With two paddles, the Home was a fast ship—had, in fact, made the journey from New York to Charleston, SC in 64 hours, setting a speed record for the run.

When she set sail from New York for Charleston on Saturday, October 7, hopes were high that the Home would again set a record.

But looming over the horizon of those hopes were the storm clouds of Racer’s Hurricane.

The storm is named for the HMS Racer, one of the first ships to report the hurricane. On September 28th and 29th in the northwestern Caribbean, the ship was dismasted and, according to reports, stood on her beam end twice. She reported force 12 winds on the Beaufort scale—hurricane-force winds.

The storm tracked northwest, crossing the Yucatan Peninsula, across the Bay of Campeche, making landfall again on what is now the U.S. Mexico border. It then did something hurricanes very rarely do—it made a U-turn, tracking east along the Gulf Coast of Texas and Louisiana, then through Georgia, exiting the mainland around Charleston, SC on October 9. Over the ocean, the storm regained lost strength and moved north and east, roughly parallel to the coast.

Although the storm was south of the Outer Banks, as is often the case with powerful tropical systems, the storm’s power was widespread. By Sunday evening, the seas were running high, and winds were rising as the Home paralleled the northern Outer Banks.

By early Monday morning, the gale-force winds were building to hurricane strength, and waves towered over the ship. According to passengers, at least two ship captains were on board as passengers, and they pleaded with Captain White of the Home to turn the ship around.

White replied that the ship was new and well built and that it could ride the storm out.

Except the ship was not that well built, or perhaps it was well built for use on rivers, but it was not designed for the ocean. When the owners had converted the Home for the sea, they had redone the interior but did nothing to strengthen the hull and frame.

As the daybreak came, the ship was leaking. Waves were washing over the ship, and water was seeping through the deck planks. Seams in the hull showed signs of distress, and the pumps were constantly running, trying to keep up with the onslaught of water.

At 2:00 p.m. Captain White pressed the crew and passengers into bailing service in a vain attempt to keep the water from rising inside the ship.

Six hours later, at 8:00 p.m., the water reached the boilers, and the engines shut down. The Home, now running with sails only, had rounded Cape Hatteras, and Captain White headed west hoping he could ride out the storm in the lee of Cape Hatteras.

But the ship, at the mercy of hurricane-force winds from the northeast and threatening to break up with every wave, headed farther south. Now Captain White was hoping to beach his ship, seeing that as the only hope to save passengers and crew.

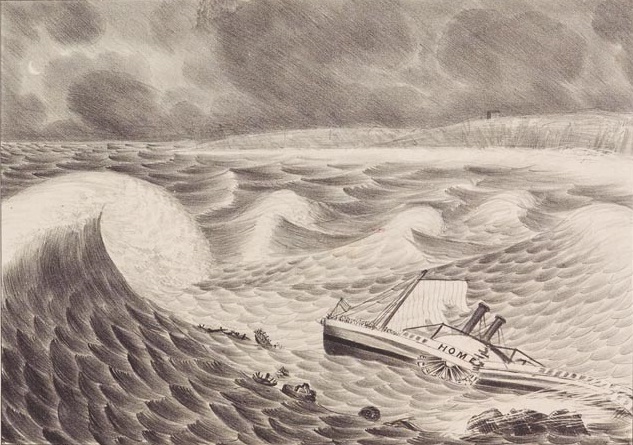

As the shoreline of Ocracoke Island could be made out, the captain turned his ship to the beach. But the Home, waterlogged and heavy, grounded a quarter-mile from shore. Waves battered her, washing over the ship, sweeping passengers, crew and everything in their path into the raging sea.

The ship was battered to splinters. One of the lifeboats was staved in before it could be launched. The other two lifeboats were launched and were quickly overwhelmed by the sea, and everyone in them lost.

Of the 130 crew and passengers that left New York that Saturday, only 40 survived. It was and is still the worst shipwreck to ever occur on Ocracoke Island.

The loss of life as the Home was battered by the sea was a combination of factors. The consensus at the time was the ship had no business sailing on the Atlantic Ocean.

Writing about the shipwreck in 1840 in his book Steamboat Disasters and Railroad Accidents in the United States, author S.A. Howard comments, “We have no evidence that in her model or timbers, any reference was had to a capacity for encountering the perils of the ocean; but candor compels us to say that her model…and other circumstances, induce the conviction that she never was intended (sic) for a sea boat.”

There were also no life preservers on the ship. Two passengers brought their own onboard, and both survived. Congress, taking note of that, passed the “Steamboat Act of 1838” which required all ships to be equipped with life preservers.